When my brother Graham was in kindergarten, he learned a little bit about Pablo Picasso. And so my mother decided to take the whole family to a touring Picasso exhibit at the Smithsonian, which featured five or so of his paintings, including some of his most famous examples of cubism.

My brother is a man of few words, and he wasn’t any different as a little boy. He quietly walked around the paintings, looking intently at them and being careful not to cross the red velvet ropes that kept out curious hands. Nearby, we were all watching Graham, wondering what in the world he was thinking.

That’s when he stepped back from one of the paintings and said, “Oh, I get it.” We waited for something insightful. He pointed to the velvet ropes and said: “The paint is still wet.”

Cubism is not the easiest kind of art to understand. But you have to admit — whether you like it or not — cubism catches the eye.

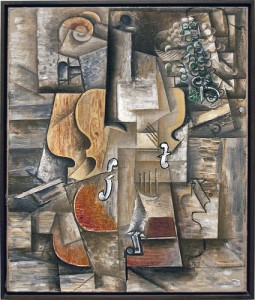

In cubism, objects are deconstructed, analyzed and reassembled — but not necessarily in their original order or size. When this is done in painting, the result is a three-dimensional object reassembled in a two-dimensional space, without regard to what can actually be seen in the real world. So while you can’t see the back of a violin when you’re looking at the front, Picasso may depict the back and front at the same time in the same two-dimensional space.

Freaky, right?

I’ll leave it to the art experts to explain why this works. But I can talk a bit about the

the geometry of cubism.

First, you need to know that cubism has its roots in the work of Paul Cezanne. He began playing with realism, saying he wanted to “treat nature by the cylinder, the sphere, the cone.” In other words, he began replicating these figures as he saw them in his subjects.

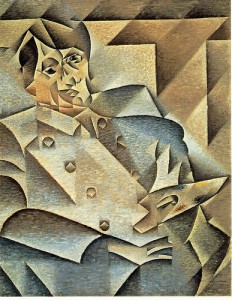

Henri Matisse, Picasso, and others took Cezanne’s approach even further. It’s not hard to recognize the cubes and angles and spheres and cones. But it’s the flattening of three-dimensional space and disregard of symmetry that really distinguishes cubism from realism or impressionism.

Symmetry is a very common occurrence in mathematics. From symmetric shapes to the symmetry of an equation (remember: what you do to one side of an equation, you must do to the other!), it’s fair to say that when symmetry is absent, it’s a big deal.

And the same is true for nature, the most often referenced subjects in art. A face, a water lily, the body, a beetle — you could spend all day finding symmetry in the natural world. Cubism turns this notion on its head.

And still, the pieces are compelling. It’s that dissonance that draws our attention and even illustrates difficult subjects. (Picasso’s most enduring and controversial pieces is Guernica, a large painting depicting the Nazi bombing of a small Spanish town.) The artists do this by breaking traditional rules and ignoring some mathematical truths.

Do you like cubism? Have a favorite artist? When you’ve seen cubism in the past, did you think of it mathematically? Buy the math books that will help you learn math for practical purposes, the math that you will use in your everyday life.

Comments are closed.