Since interviewing Elizabeth Perkins for Math at Work Monday, I have been obsessed with the process of glass blowing. I’ve watched videos and read about the step-by-step process. I still don’t know much — this stuff is complicated! — but there are a few little math connections that I made here and there, and I thought I’d share them with you.

First off, there are the tools. The steel pipe that holds the glass is a very long cylinder or straw. The hole allows the artist to blow air into the glass at one end, which creates the bubble.

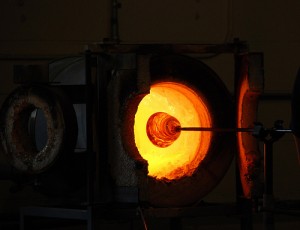

Then there are not one, not two, but three furnaces. Why three? Because the entire process requires different levels of heat. The first furnace contains molten glass. The second, called the “glory hole” is used to reheat the piece as it’s being formed. And the third, which is called the “lehr” or “annealer” is used to cool the piece very slowly and deliberately so it maintains structural soundness.

The artist is constantly working against temperature changes. When the glass is in liquid or semi-solid state, its shape can be changed, and this is accomplished by spinning the pipe. To achieve a symmetric shape, the glass must be spun in consistent circles. This is where the bench comes in. The glass blower can place the pipe along two parallel arms and push the pipe out and in. Because the arms are parallel and the same height from the floor, the glass can be spun consistently.

Okay, so we have some geometry (the pipe and the bench) and measurement (the furnaces regulated at different temperatures).

Time for more geometry. After the glass blower gathers a layer of glass on the end of her pipe from the first furnace, she rolls it on a table to give it a cylindrical shape. Blowing into the pipe creates the bubble — which eventually will become the curve of a bowl, glass, lampshade or something altogether different. How that bubble is formed is critical to the stability of the piece. The glass must be thicker around the bottom and thinner along the sides.

And this is where things get really mathy. See, the bubble at the end of a glass blower’s pipe is usually some kind of ellipsoid. You already know what an ellipsoid is. You live on one: planet Earth. An ellipsoid is like a slightly flattened sphere. In fact, a sphere is a special kind of an ellipsoid.

After the glass blower completes the piece, it goes into the annealer, which is programmed for that particular piece of glass. Some pieces need to cool more slowly than others, and that cooling process is dictated by math.

So there you have it — my very uneducated look at the math of glass blowing. You too can see math in everything, if you just look closely enough.

Are you noticing math in art? Share your observations in the comments section.

Comments are closed.