anyone lived in a pretty how town (with up so floating many bells down) spring summer autumn winter he sang his didn't he danced his did

So goes my very favorite poem, written by e.e. cummings. In my senior year of high school, I wrote a term paper explicating the verse, and I fell in love. At the same time, I was taking two math classes, and somehow the process of solving a system of equations was similar to understanding cummings’ strange syntax and playful turns of traditional poetic forms.

April is not only Math Awareness Month but also National Poetry Month. In a facebook conversation with another writer, I found myself offering to show the connections between math and poetry — a task that is surprisingly simple but (if similar articles and blog posts are any indicators) could be very contentious. I like a challenge and a good intellectual fight, so here goes:

Symbols

I’ve long asserted here that mathematics is a language that describes the physical world. Without mathematics, we cannot describe physics. And mathematical models allow us to predict the future or see the invisible. Math also depends heavily on symbols — variables, Greek letters and characters that represent operations like addition and division.

Clearly, symbolism is the very basis of poetry. When Robert Frost writes, “Two roads diverged in a yellow wood, / And sorry I could not travel both” he doesn’t mean that he is literally sorry that he cannot literally travel two literal roads. Nope. The yellow wood represents the later years of the poet’s life when he’s considering the choices (roads) he could have made (taken). (For sure, there are many versions of this interpretation.)

The same is true for the symbolism in math. When you graph a curve that represents the steady increase of your take-home pay over several years, the curve is a symbol of your financial (and perhaps professional) success. But you can interpret or apply the curve in a variety of different ways, and the curve doesn’t tell the entire story.

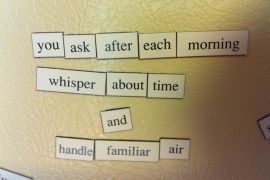

[laurabooks]

Patterns

You can’t deny the patterns found in mathematics. All you need to do is list multiplication facts for a certain number, and a structure will jump off the page or computer screen. (Eventually.) Then there are a variety of sequences and series, like Fibonacci’s Sequence (1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, …) or a geometric series (like 1 + 2 + 4 + 8 + …).

The patterns in poetry are often found in meter and rhyming schemes. So the first line of Shakespeare’s Sonnet 73 is in iambic pentameter: “That time of year thou mayst in me behold.” We know this because it features five two-syllable feet that are expressed as non-stress, stress. (In other words: “That time of year thou mayst in me behold.”) Along with iambic, traditional poetry may follow trochaic, spondaic, anapestic or dactylic meters — but there are endless more styles. Cummings’ “anyone lived in a pretty how town” is generally considered to be a ballad, which, when you know the key that unlocks the poem’s meaning, makes perfect sense.

Symmetry

The idea that two halves are symmetric is not mandatory in mathematics or poetry, but oftentimes it takes center stage. In math, we have symmetric shapes, like circles or isosceles triangles. Symmetry is also critical in solving equations, as you must do the same thing to both sides of the equation.

And in poetry, symmetry is often found in the ways that verses and stanzas are structured. “The Road Not Taken” features four stanzas with five verses each.

Two roads diverged in a yellow wood, And sorry I could not travel both And be one traveler, long I stood And looked down one as far as I could To where it bent in the undergrowth; Then took the other, as just as fair, And having perhaps the better claim Because it was grassy and wanted wear, Though as for that the passing there Had worn them really about the same, And both that morning equally lay In leaves no step had trodden black. Oh, I marked the first for another day! Yet knowing how way leads on to way I doubted if I should ever come back. I shall be telling this with a sigh Somewhere ages and ages hence: Two roads diverged in a wood, and I, I took the one less traveled by, And that has made all the difference.

Many mathematicians and poets have pointed out even more similarities (some that, in my opinion, suck the life and art out of both math and poetry), but these are some basic ideas. I’ll leave you with what Einstein said on the matter: “Pure mathematics is, in its way, the poetry of logical ideas.” To which I say: math and poetry are designed to give the illogical some kind of logical shape.

There are some really interesting everyday life math examples in my books. Visit this page and buy the book today!