I am an INTP — introvert, intuitive, thinking, perceiving. If this is all Greek to you, let me be the first to introduce you to the Meyers-Briggs Personality Type. According to the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), this combination of letters means I am conceptual, analytical, intellectually curious, adaptable, independent and critical. I love ideas and pursue understanding.

Sounds exactly like me. Exactly.

I learned my Meyers Briggs personality type by taking a rather involved multiple-choice evaluation. But there are shorter tests online that work reasonably well. If you don’t know your type, check it out here. (I’ll wait.)

It’s pretty trendy to know what your personality type is and to identify the characteristics that you share with others. Being an INTP — remember, I love ideas and pursue understanding — I think this is a really good thing. (Also being an INTP, I think it’s a good idea for folks to get the real Meyers-Briggs test, if they plan to use the results in any serious capacity, like workplace team building or couples therapy.) You don’t have to agree with the veracity of these personality types to find them interesting and entertaining. Personally, I’ve found that knowing my type helps me make decisions — like striking out on my own as a freelance writer.

But what I find in the many, many articles on this subject is how unique the results seem. So many of my friends have said, “Wow! No wonder I feel so [misunderstood/alone/different]! Only 5 percent of the population has the same personality type as I do!”

On some level, and with some things, we all want to feel singular. Seems to me, personality types are one of those things.

But these small percentages have always bugged me a little bit. And that’s because of the math.

There are four preferences in the Meyers-Briggs personality type: introversion vs. extroversion, sensing vs. intuitive, thinking vs. feeling, and judging vs. perceiving. (I won’t get into the details of these characteristics, but do know this: judging isn’t a bad thing at all. Learn more at The Meyers Briggs Foundation website.) Since there are two options per preference, there are 16 possible personality types according to the Meyers-Briggs test.

I think we forget that there are so many different combinations. And that clouds our understanding of what is rare and what is not rare.

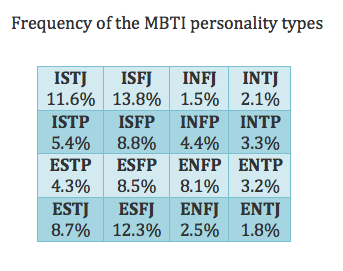

In fact, the Meyers Briggs Foundation has studied the occurrence of each of the 16 personality types in the population.

First, a disclaimer: already, this is not a random sample. The foundation used data that is reported to them, which means that only people who have taken the MBTI evaluation were in the sample studied. But what if people with a certain personality type are less likely to take a personality test? This type would not be accurately represented in the sample. And if one type is more likely to take a personality test? Those folks might appear more often in this sample than in the general population.

Still, let’s take a look.

If you lined up all of the personality types in order of their percentages, the types at the middle are ISTP (5.4 percent) and INFP (4.4 percent). If you fall within 5 percent of the population, are you unusual? Well, yes. In some regard, but only if the rest of the population falls in one category outside of that 5 percent.

In terms of rarity, we often think of rates of disease. According to the American Autoimmune Related Disease Association, about 5 percent of the population in Europe and North America have an autoimmune disease. With these diseases, (including celiac disease, rheumatoid arthritis, multiple sclerosis, lupus and type I diabetes) the immune system is attacking some part of the body. (In fact, my father had autoimmune hepatitis and vitiligo and died of pulmonary fibrosis.)

If 5 percent of the population is affected by autoimmune disease, 95 percent is not. This makes autoimmune disease seem kind of usual or rare. Actually, it’s not rare by medical standards. For a disease to be considered rare in the U.S., it must affect less than 0.06 percent of the population.

And as with all math, the context matters. There are 16 personality types. If there were only three types, 5 percent is really rare. But with 16 types, well, 5 percent isn’t so unique. That’s because the other 95 percent is spread out among the remaining 15 types.

Now where this stuff gets really interesting is in certain populations. For example, in a 1992 study of college and research librarians, 11.5 percent were INTJ, while 0.8 percent were ESFP. These results definitely don’t square with the frequency in the general population. So you might be not so rare among librarians but more uncommon within the rest of the world.

I don’t mean to suggest that each of us is not a special snowflake. We are — but that’s not because of our personality types. As useful as these categories are, they certainly ignore a large part of the rest of what makes us who we are. (Meyers and Briggs knew this, of course, and their foundation works hard to be sure that the MBTIs are used ethically and responsibly.)

So go on with your special self. Fly your freak flag proudly. Just know that each of the personality types is interesting and unique in its own way. You are special, but not because of your personality type. There are just too many other possibilities!

Photo Credit: db Photography | Demi-Brooke via Compfight cc

Do you know what your MBTI type is? I love to hear about others’ personality types and how they understand them. Share your personality type stories in the comments section. Because you’re special. Just the way you are.