When you were in middle and high school, did you think you’d

never need to use the math you were learning? Like most grownups, you

probably found out that, yes, you did need some of it — and some of it

you’ll never do again.

Each Monday, I’ll introduce you to someone who uses math on the

job. We’re going to skip over the engineers, physicists and

statisticians and stick to folks who use regular, everyday math. First

up, my sister, Melissa, a speech therapist.

So, what kind of speech therapist are you, and how long have you been doing this job?

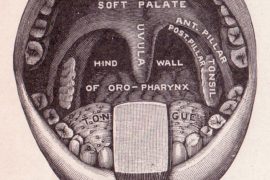

Lots of people think of speech therapists in the school setting,

working with kids. But I work with adults, who are critically ill or

recovering from an injury or illness in rehab. I’ve been doing this for

19 years. Basically, I provide care in these areas:

- Speech and communication: patients who have declined neurologically or physically and cannot talk, have slurred speech, or any difficulty communicating.

- Swallowing: patients who have swallowing impairments, usually from neurological deficits, or physical decline in some way.

- Cognitive: patients whose thinking skills have declined, including memory, problem solving, attention, reasoning.

- Other specialty areas: patients with tracheotomies, laryngectomies, concussions.

All of my patients are adults, and most of them have had some sort of illness or injury.

When do you use math in your job?

Rehab is very goal oriented. I meet with patients on a regular basis and keep data on those goals — how many questions the patient answered correctly or the number of times a he performed a certain task properly. At the end of the day, I tabulate that data. And then at the end of the week, I average the data for the week.

I also use math in some of my tasks with the patients.

Functional math is a form of reasoning, and so I will provide a patient

with math tasks to “rehab” his or her reasoning skills.

These calculations help me determine if the patient has met that goal, and if so, I create a new goal.

I also use math in some of my tasks with the patients. Functional

math is a form of reasoning, and so I will provide a patient with math

tasks to “rehab” his or her reasoning skills.

What kind of math is important for your job?

Percents! If the patient got 8 out of 10 correct on a certain task, I

put in the note that she was 80% successful. (But sometimes the numbers

aren’t great for mental math: 29 out of 44 correct, for example.)

Most rehab and acute care settings use a very specific form of

measuring assistance, called Functional Independent Measures, or FIMS.

- Independent: 100%

- Modified Indpendent: 100% with extra time

- Supervision: 90% or above

- Minimum Assist: 75-90%

- Moderate Assist: 50-75%

- Maximum Assist: 25-50%

- Dependent: less than 25%

So, since I measure FIMS weekly, I am always creating percentages in my head (and on paper) of how a patient is performing on that certain task.

How does math help you do your job?

It allows me to be very accurate in data collection. Of course, many patients’ lengths of stay is dependent

on whether or not there is proven progress, and the best way to prove

it is to show it in black-and-white. Patients and their families would

rather see “80% accuracy” as opposed to “required min assist.” Percents

are more accurate and detailed.

I also firmly believe that having patients do math themselves helps

them building their reasoning skills. I think I am doing my job better

by making them do math! I will even have my patients average their data

for the week. This helps them use reasoning skills as well as

understand their goals and how they are progressing.

How comfortable with math do you feel?

I feel comfortable with simple math, especially if I can write it

out, use pen and paper, etc. I get bogged down with more complex actions

and definitions, but I don’t have to use these in my job.

Did you have to learn to use new skills?

No, I use basic elementary and middle school math. However, I do feel

like it took me years in my job to realize that I could involve the patient to help me! It’s a great way to help the patient therapeutically. I think I forget to make math functional.

Thank you, Melissa for being the first person featured in Math at Work Monday!

If you have questions for Melissa, feel free to ask them in the

comments section. And if you know of someone who uses regular math in

their jobs — duh, of course you do! — and you would like to see that

person featured here, drop me a line and let me know!