I know what you’re thinking. “It’s so obvious how a 6th grade teacher would use math! She’s teaching fractions and division and percents!”

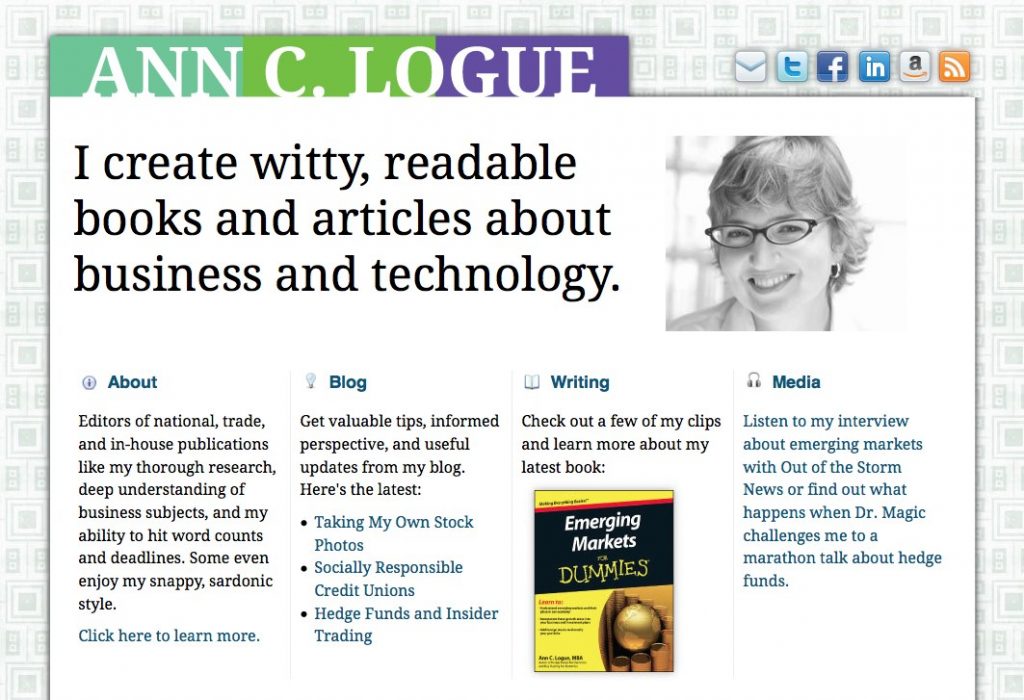

There’s always a lot more to teaching than the rest of us may think. And that’s why I asked Tiffany Choice to answer today’s Math at Work Monday questions. Ms. Choice was my daughter’s 4th grade teacher, and she’s the best elementary math teacher I’ve ever met. She truly made the math fun, and she really got into her lessons. I know this for sure, because I had the pleasure of subbing for Ms. Choice while she was on maternity leave. Let me tell you, those kids loved her — and so do I!

Last year, Ms. Choice moved to Fairfax County, Virginia. She’s getting ready to start teaching 6th grade there. In honor of what was supposed to be our first day of school — until Hurricane Irene changed our plans! — here’s how she uses math in her classroom.

Can you explain what you do for a living? I teach state-mandated curriculum to students. My job also includes communicating to parents progress and/or concerns, appropriately assessing my students, and analyzing data to drive my instruction and lessons.

When do you use basic math in your job? I use math all the time — mostly basic addition, subtraction, multiplication and division. When I plan lessons, I need to appropriately plan for activities that will last a certain length of time. Then, when I am teaching the lessons, I am watching the clock and using timers to keep my lessons moving or calculating elapsed time.

I also use math to grade assignments and calculate grades. I break a student’s grade into 4 categories; participation, homework, classwork, test/projects. Each category has a different weight. Participation and homework are each 10 percent, while classwork and test/projects are each 40 percent. Then for each grading period, I average grades and take the appropriate percentage to get the overall grade.

I also use math to analyze data and drive my instruction. After quarter assessments or chapter tests are given, I look for trends. Which questions did the majority of students get incorrect? If I notice out of 60 students only 30% of them got a certain question correct this says to me that most of them (42 to be exact) got the question wrong. I need to figure out why and go back.

I will also use math to group my students for games and activities. When I originally plan for them I always assume all students will be present. However, with absences and such I have to use last-minute division to regroup them. I move desks around into different groups periodically during the year, and that requires division as well.[pullquote]It’s completely normal to feel anxious or nervous about math. But a great teacher at any level (primary to college) will help you “get it.” Just don’t give up.[/pullquote]

When I plan for field trips, I have to calculate the total cost for each student depending on the fees involved. Then, I have to count large amounts money that has been collected to account for the correct amounts.

Do you use any technology (like calculators or computers) to help with this math? At my first teaching job, I had a computer program that calculated grades for me, but when I left and went to a new district I didn’t have that software, so I did grades all by hand using a calculator.

How do you think math helps you do your job better? The whole point of my job is to get students to learn and become great thinkers. I wouldn’t be able to find or focus on areas of weakness if I wasn’t able to properly analyze data and comprehend what it really means to me.

What kind of math did you take in high school? Did you like it or feel like you were good at it? I only took algebra and geometry in high school. I was terrible at math in high school and didn’t enjoy it or “get it” until college. I started in a community college and I had to take two developmental math classes before I could take what was required. It was during those developmental courses I finally “got it” and began to actually enjoy it. Everything finally made sense.

It’s completely normal to feel anxious or nervous about math. But a great teacher at any level (primary to college) will help you “get it.” Just don’t give up.

Did you have to learn new skills in order to do this math? The math I use to do my job is math that is taught up to the middle school level. I didn’t have to learn anything special.

Thanks so much, Ms. Choice! (I don’t think I can ever call her Tiffany!) If you have questions for Ms. Choice, just ask them in the comments section. She has agreed to come back to Math for Grownups to talk a bit about how parents can work with their kids’ math teachers, so stay tuned for more advice from her.