When it comes to basic calculations, kids can benefit from knowing math facts cold. When the arithmetic is simple, we can focus on more complex concepts.

That’s one reason your children are encouraged to memorize their multiplication tables. But over the years, educators have discovered that straight memorization is not always the best. In fact, when kids spend a great deal of time really unpacking what these math concepts mean, they’re far more likely to expand their understanding of many other concepts.

So are math “tricks” a good thing or a bad thing?

“Kids should have a way of figuring out the math fact that uses reasoning,” says Dr. Felice Shore, assistant professor and co-assistant chairperson of Towson University’s math department in Maryland. As an expert in mathematics education, Shore knows that when children’s natural curiosity is stimulated, they can make important mathematical connections that will deepen their understanding.

“But once kids can reason their way to the answer and understand various ways to do so, these ‘tricks’ can help them get answers quickly,” she continues.

The key is to introduce these tricks at the right age.

“I don’t think the third or even fourth-graders should learn tricks,” Shore says. “The important mathematics at those grades is still about building an understanding of relationships between numbers—the very reasons behind math facts. Once you show them the trick, it’ll most likely just shut down their thinking.”

But math tricks can be useful. If your fifth grader is still struggling with her multiplication tables, these can be a godsend. Even better is when they reveal something about the math that makes them work.

If you’re going to show your child a quick way to multiply, make sure that you help her understand why the trick works. Here are five cool examples—and the math behind them.

[laurabooks]

Multiplying by 4

This trick is so simple and logical, that it could hardly be called a trick. But it could come in handy for your budding Sir Isaac Newton. To multiply any number by 4, simply multiply it by 2 and then double the answer.

35 x 4

35 x 2 = 70

70 x 2 = 140

35 x 4 = 140

Why does it work?

This trick is based on a very simple fact:

2 x 2 = 4

That means that:

35 x 4 = 35 x (2 x 2)

And

35 x 2 x 2

70 x 2

140

The underlying lesson of this “trick” is that you can solve a multiplication problem by multiplying by its factors.

Multiplying by 9

Hold up both hands, with your fingers spread. To multiply 4 x 9, bend your fourth finger from the left. Count the number of fingers to the left of your bent finger—you should get 3. Then count the number of fingers (and thumbs) to the right of your bent finger—you should get 6. The answer is 36. This works when multiplying any number 1-10 by 9.

Why does it work?

Simple algebra can show that what you’re doing with your fingers boils down to this: When you multiply by 9, you’re really multiplying by 10 and then subtracting that number. But you don’t need to do the algebra. Some kids figure out that reasoning without the mysterious finger trick.

You can help your child extend her understanding of the number 9 by pointing out an important piece of this trick: in the 9s multiplication tables, the digits add up to 9!

4 x 9 = 36 —> 3 + 6 = 9

9 x 9 = 81 —> 8 + 1 = 9

Then you can prompt your child to notice other patterns. For example, 4 -1 = 3 and 3 + 6 = 9 and 4 x 9 = 36. The patterns in the 9s multiplication tables are endless and can lead to many other discoveries about numbers.

Multiplying by 11

Sure, multiplying a one-digit number by 11 is a cinch.

4 x 11 = 44

7 x 11 = 77

But did you know there’s a trick to multiplying any number by 11? Here’s how using an example: 52 x 11.

The first digit of the answer will be 5 and the last digit of the answer will be 2. To get the digit between, just add 5 and 2.

5 (5+2) 2

572

You may have noticed that when you add the two digits together, you get a one-digit number. If you get a two-digit number, things are a little trickier.

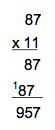

87 x 11

8 (8+7) 7

8 (15) 7

(8+1) 57

957

Why does it work?

If you think of doing long-hand multiplication by stacking the two numbers, you’ll see right away:

But the more precise reasoning has to do with place value. What you’re really doing is multiplying 87 by 1, then multiply 87 by 10, and finally adding the two products together:

87 x 1 = 87

87 x 10 = 870

870 + 87 = 957

The trick itself is just a shortcut to the answer.

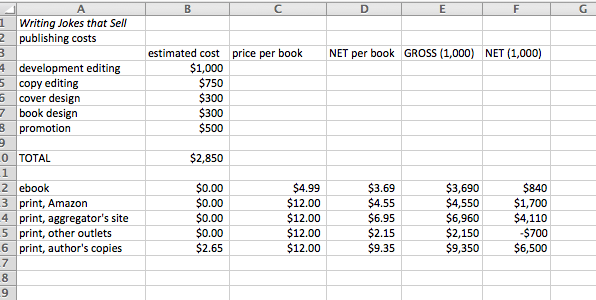

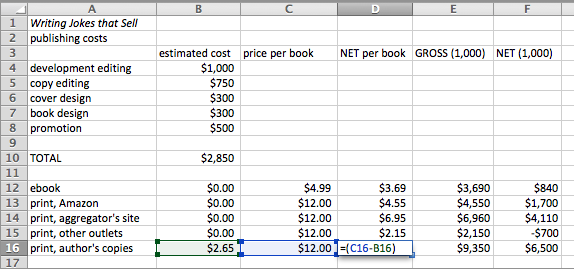

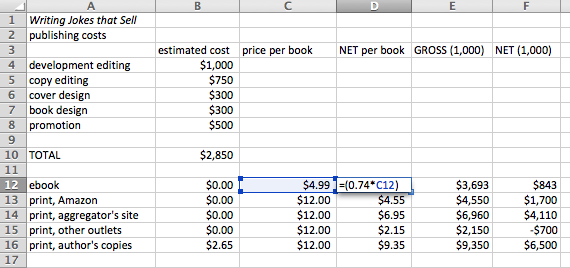

Multiplying by 12

Just like the previous track, you can multiply any number by 12 very quickly and easily. Let’s try it with 7 x 12.

First multiply 7 by 10. Then multiply 7 by 2. Finally, add them together.

7 x 12

7 x 10 = 70

7 x 2 = 14

70 + 14 = 84

Easy peasy. When this gets really impressive is with larger numbers.

25 x 12

25 x 10 = 250

25 x 2 = 50

250 x 50 = 300

Why does it work?

This trick works for the same reason that the 11s trick works. But there’s another way to describe it. Think of 12 as the sum of 10 and 2.

25 x 12

25 x (10 + 2)

(25 x 10) + (25 x 2)

250 + 50

300

Is a number divisible by 3? (Or in math terms: Is a number a multiple of 3?)

When a number is evenly divisible by another number it is said to be a multiple of that number. In other words: since 27 is evenly divisible by 3, 27 is a multiple of 3.

Turns out, there’s a nice little trick for this as well. Add up the values of the digits. Is that sum a multiple of 3? If so, the number itself is also evenly divisible by 3. Check it out:

Is 543 divisible by 3?

5 + 4 + 3 = 12

12 is divisible by 3

So 543 is divisible by 3

Why does this work?

Place value is key here, but there’s an easy way to show your child what’s happening before you even introduce the trick. Do this with something tangible, like M&Ms or pieces of cereal.

- Start with 45 candies.

- Have your child divide the candies into two piles based on the place value—one pile of 40 candies and one pile of 5 candies.

- Now ask your child to divide the 40 candies into groups of 10 candies. (She should notice that there are four groups of 10 candies.)

- Now ask her this question, “How can you change each of these groups often, so that the number is divisible by 3?” She should suggest that you take away one candy from each pile. (If not, coax her to that answer.)

- Have her take one candy from each group of ten and move them into another group.

- Point out that she has six piles of candies: four piles of 9 candies, one pile of 4 candies and one pile of 5 candies.

- Ask her what happens if she combines the pile of 4 candies and the pile of 5 candies. She should notice that she’ll get 9, which is divisible by 3.

- By now, she will probably notice that the 4 and 5 come from number 45. See if she can come up with the trick, after doing this with a few examples using the candies.

So what do you think? Are math tricks a good idea or not? Do you have any other tricks to share? And can you explain why they work? If you need help with your math, I have written these great books to help you learn the easy way.