On Monday, I introduced you to Elizabeth Perkins, an up-and-coming glass artist in Seattle. (She also happens to be one of my former students, but that is mere coincidence. I take no credit whatsoever for her success and talent.) In her interview, she mentioned that she depends on the Fibonacci sequence to develop some of her annealing programs, or processes for cooling the glass so that is remains structurally sound.

But what the heck is a Fibonacci sequence?

Well, it’s a pretty cool list of numbers. And it’s also really, really easy to figure out. See for yourself:

0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13, 21, ?

What’s the next number?

I’ll give you a chance to think about it.

Need a hint? Pick any number in the list (except for the first 0 and first 1), and look at the two numbers before it.

Get it yet? (The correct answer is 34.)

The Fibonacci sequence is generated by adding the last two numbers together to get the next number. Take a look:

0 + 1 = 1

1 + 1 = 2

1 + 2 = 3

2 + 3 = 5

3 + 5 = 8

5 + 8 = 13

8 + 13 = 21

13 + 21 = 34

Now that you know this rule, you could conceivably add numbers to this sequence until you got bored or exhausted (which ever comes first).

The fellow who discovered this sequence was, you guessed it, Fibonacci — an Italian mathematician and philosopher who was reportedly born in 1175 AD. But to be honest, his sequence is not the greatest contribution Fibonacci (or Leonardo de Pisa) gave to humankind. In fact, he is the father of our decimal system. Yep, the fact that you can count the $5.23 you have in your wallet is due to a guy whose real name we don’t even know for sure.

But I digress.

The Fibonacci sequence isn’t just an easy and cool math fact. It’s cool — and really, really important — because it shows up everywhere. Here are just a few examples:

If you count the petals of various species of daisies, you’ll get one of the Fibonacci numbers.

The length of the bones in your wrist and hand are a Fibonacci sequence.

The spiral of a pineapple is arranged in Fibonacci numbers.

Branches of a tree grow in a Fibonacci sequence (one branch, two branches, three branches, five branches, and so on, moving up the height of the tree).

The gender of bees in reproduction mirrors the Fibonacci sequence.

And then there’s art. Art loves the Fibonacci sequence. Since the Greeks formalized what is beautiful in architecture and paintings, this little list of numbers has been front and center in a variety of artistic fields.

For example, this seven plate print is gorgeous and also represents something called the golden spiral. The sides of each square (starting in the center with the smallest squares) correlate to the numbers in the Fibonacci sequence. So, the smallest square has side length of 1 unit, the next largest is 2 units, the next is 3 units, the next is 5 units, etc.

Cool huh?

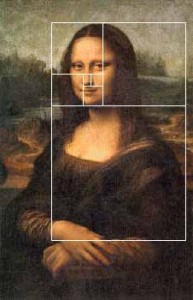

It gets better. Remember the lady with the mysterious smile? Leonardo da Vinci was fascinated by mathematics, and some folks have noticed that his lovely lady’s facial characteristics follow the path of the Fibonacci sequence.

Do you see how the squares line up with the base of her eyes and bottom of her chin, and surround her nose perfectly?

So there you have it. What we see as beautiful could very well be because of mathematical wonders like Fibonacci’s sequence. And as Beth the glass blower shows, this magical little list of numbers is useful in the science of making art as well.

Earlier this year, I posted a really, really cool video about the Fibonacci sequence in nature. Check it out here.Save